Email is a medium most of us had written off when social media came around. Yet, as a small business owner there is not a more powerful marketing tool than a well-maintained newsletter list. I'm an avid Twitter user too and I do get a lot of referrals from re/tweets, but it pales in comparison to the visits, sales, and replies I get from email campaigns. (By the way, Facebook as a promotional tool is completely useless unless you are willing to turn your messages into paid ads which, in my opinion, always feels a bit disingenuous.)

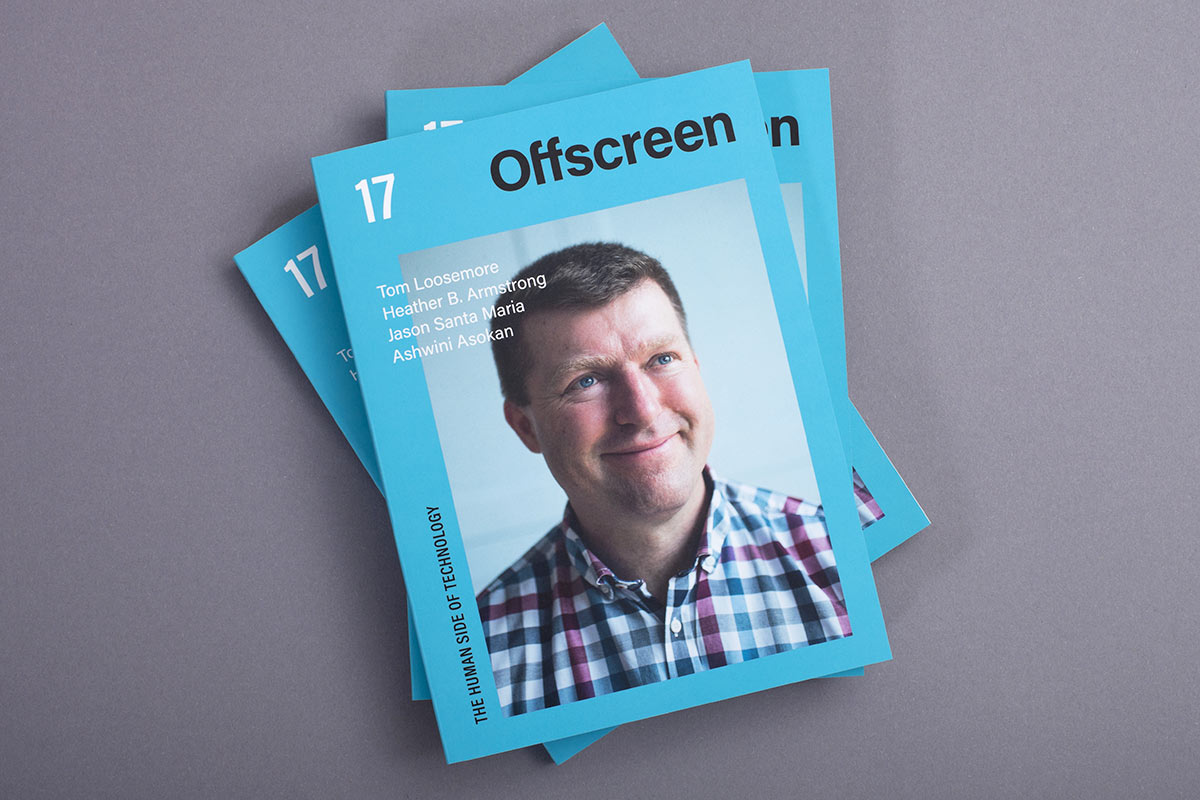

For the launch of issue 17 I sent out an email to the ~10,500 people on my 'Offscreen Updates' list. This list is separate from my weekly Dispatch list and I usually only email subscribers of that list once or twice in between issues to inform them about the status of the next issue. If you have ordered anything from the Offscreen website in the past, you've been added to that list automatically. As such, this list consists of current and past customers – some are just following along passively, some buy issues occasionally, some are active subscribers of the magazine.

Four months in between issues is a long time to remember what you last ordered, so I use my launch newsletter to inform everyone about their individual order or subscription status. Here's how I make that email as relevant and clear as possible...

Disclosure: I'm using MailChimp, a current Offscreen sponsor, for my newsletters. It's possible to achieve similar outcomes with all major email marketing providers. This post was not commissioned or paid for by MailChimp.

Adding merge tags to the subscriber list

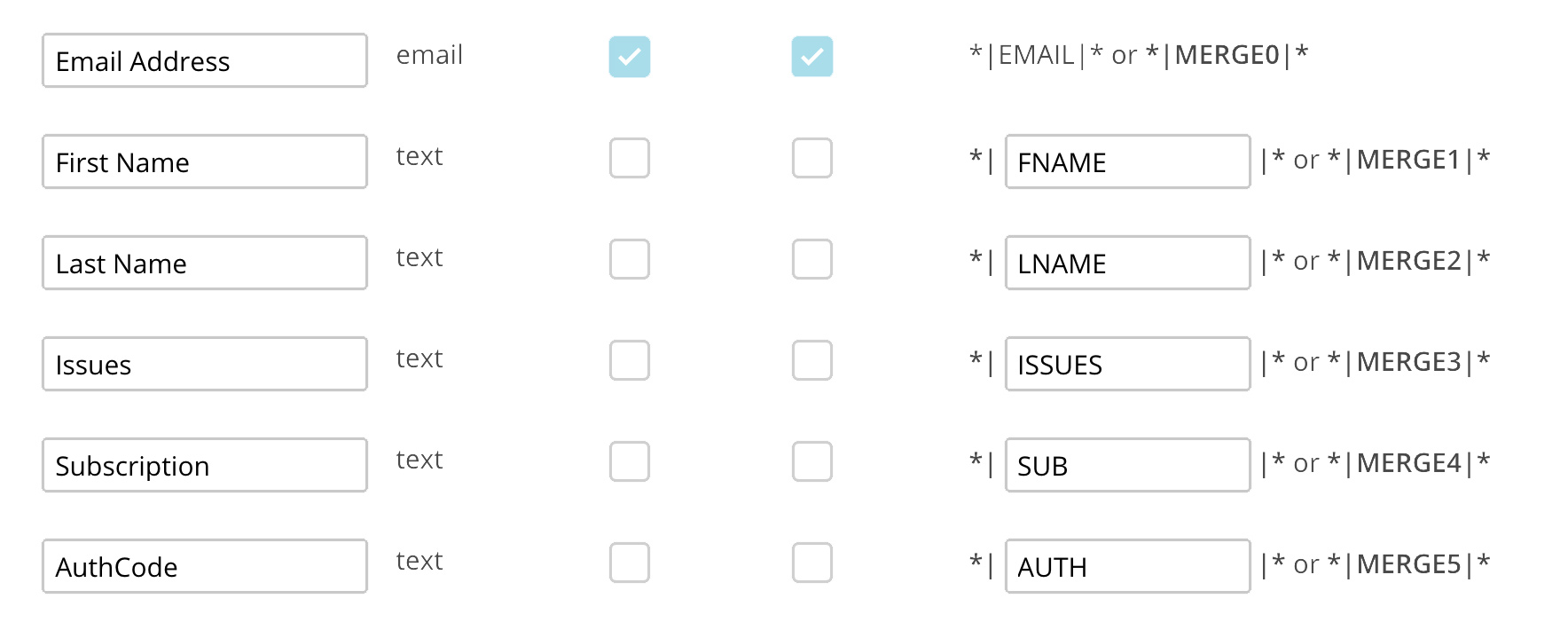

My custom order management system is connected to MailChimp via their API. This allows me to sync the following data about each customer to my MailChimp list:

Besides the obvious ones, like email and name, I also sync the number of the issues they bought (ISSUES), the type of subscription they have (SUB) and an authorisation code (AUTH). The auth-code is a string of numbers and letters unique to each customer. I use this auth-code to enable existing customers to log into their Offscreen account, but I can also use this code to send them to the Offscreen checkout page with their shipping details pre-filled.

List segmentation

I use MailChimp's list segmentation feature in conjunction with merge tags to split the list on two major groups:

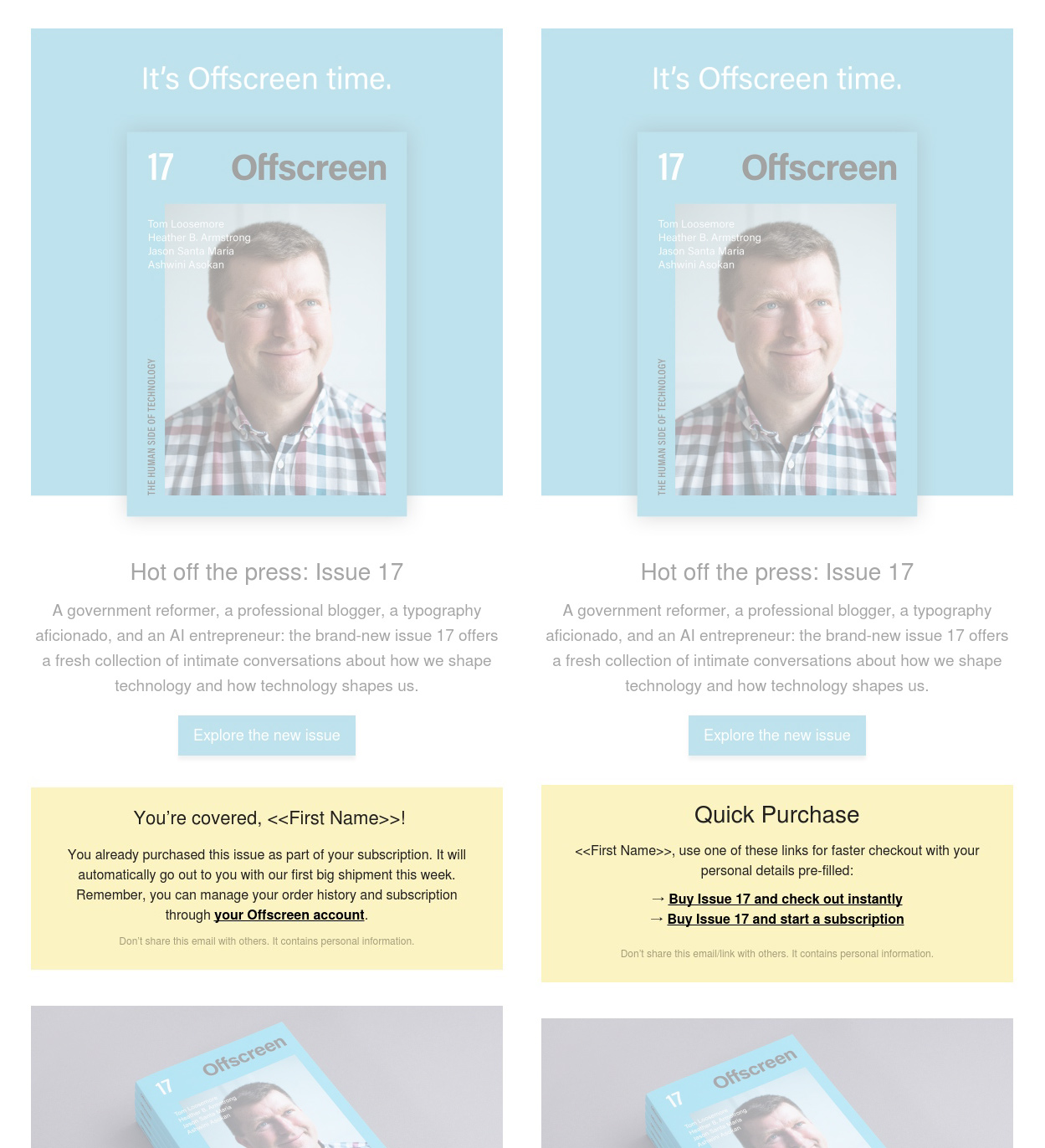

Group A: those who have already ordered issue 17.

Group B: those who have not (yet) ordered issue 17.

I then create two slightly different email campaigns for each group.

Existing customers and active subscribers to the magazine (Group A)

All customers who have already ordered and paid for issue 17 (e.g. active subscribers) receive an email that shows the following note:

Here's where the auth-code comes in handy because I can include a link to the customer's account – no login required.

Past customers and passive newsletter subscribers (Group B)

For those who have not (yet) bought the latest issue, I display a call to action to purchase the issue and/or subscribe. I split this group into two more sub-groups: 1) those who have previously ordered something on Offscreen and have an existing auth-code, and 2) those who haven't bought anything before and are just following Offscreen as a newsletter subscriber.

All customers since our relaunch have an existing account (auth-code) and so I can add their auth-code to the checkout URL which pre-populates the order form with all their shipping details. This speeds up the checkout process – they just have to add their credit card or PayPal account credentials.

Those newsletter subscribers who haven't bought anything recently get a standard set of links without any pre-filling magic.

And that's pretty much all. I think getting a clear status update about your previous order/subscription goes a long way in regards to a great customer experience. If you know a little bit about email marketing and merge tags then the above won't seem overly fancy to you. It just requires an email list that is in sync with your customer database. If you never heard of merge tags before, here's a quick intro by MailChimp. I can highly recommend using them to make your newsletters more relevant and useful to your subscribers. Happy emailing!