People often ask me what resources I can recommend for fledgling magazine makers. So here’s a list of sites and services that helped me when I got started and some others I discovered in the years that followed.

magCulture

Probably the most popular and most established blog about everything magazine related. I admire Jeremy Leslie’s persistence and devotion to the subject matter. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram too.

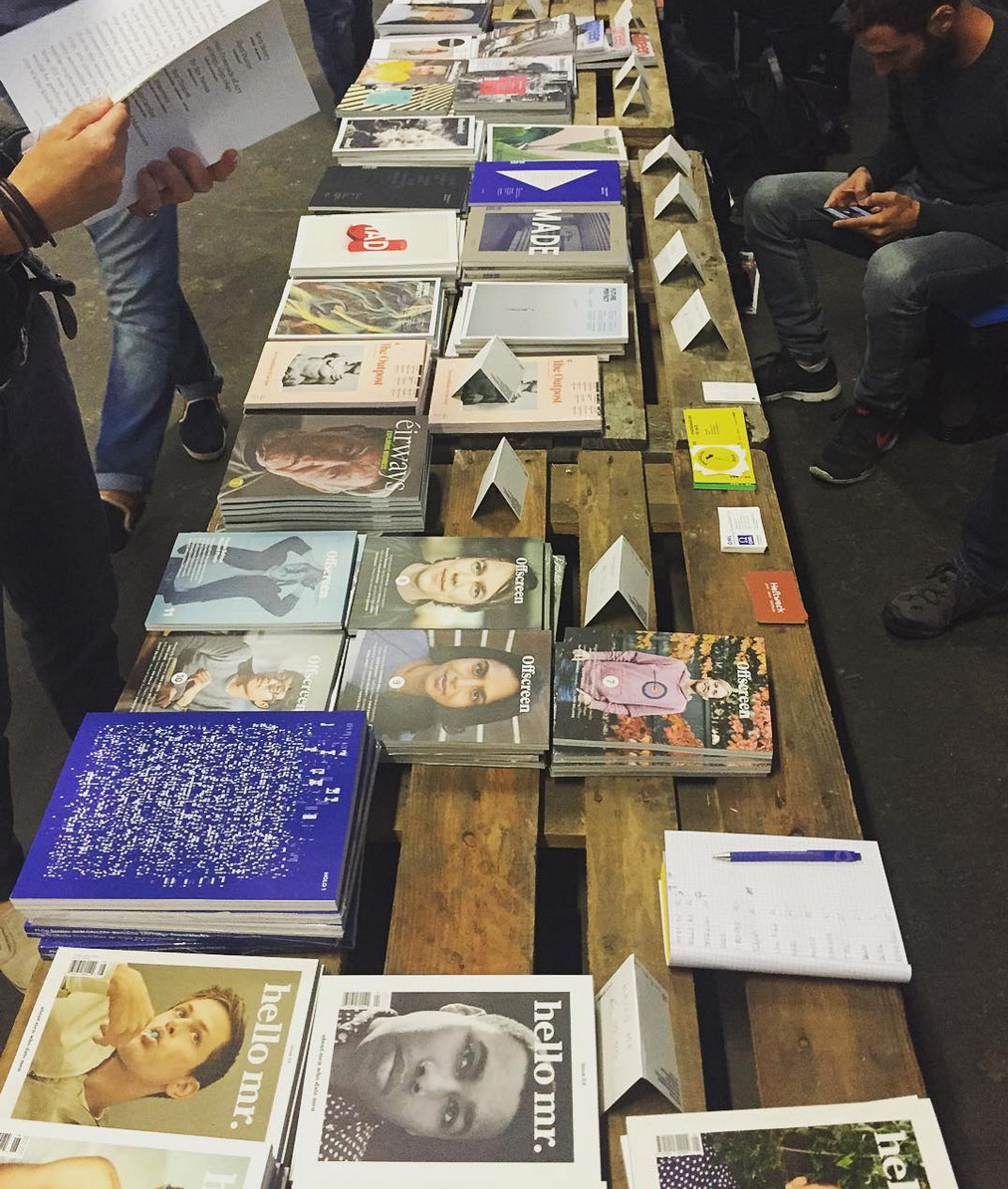

Stack Magazines

Stack is a service that sends you a random indie magazine every month. The guy behind it, Steve Watson, is also extremely knowledgable about magazines and runs a very lively blog and Twitter account with lots of mag reviews and insightful interviews.

Magpile

An online community all about magazines. Create a digital database of your own physical mag collection, follow other mag lovers, buy or sell issues and generally discover great publications (maybe by their covers?. I love what Dan is doing with Magpile! Make sure to also check out his podcast MagHeroes for interviews with publishers and his new tool for managing subscriptions, Subsail.

Magazine Wall

A Tumblr with thousands of magazine covers.

The Publishing Playbook

Hüman After All is a London-based creative agency with a lot of publishing experience (having created titles like Little White Lies and more recently Weapons of Reason. They’ve launched numerous publications in the past and have compiled their experience in this open and free Google document that is collaboratively edited by lots of other folks in the publishing community. Definitely check this out if you’re thinking of starting a magazine!

Monocle’s The Stack

The Stack is a weekly podcast dedicated to the world of magazines, often hosted by Tyler Brûlé himself.

Lynda Video Tutorials

If you’re a total noob like I was and don’t even know how to use Indesign or how colour management works (who the hell knows!?), you can use an online video tutorial service like Lynda to learn the necessary basics.

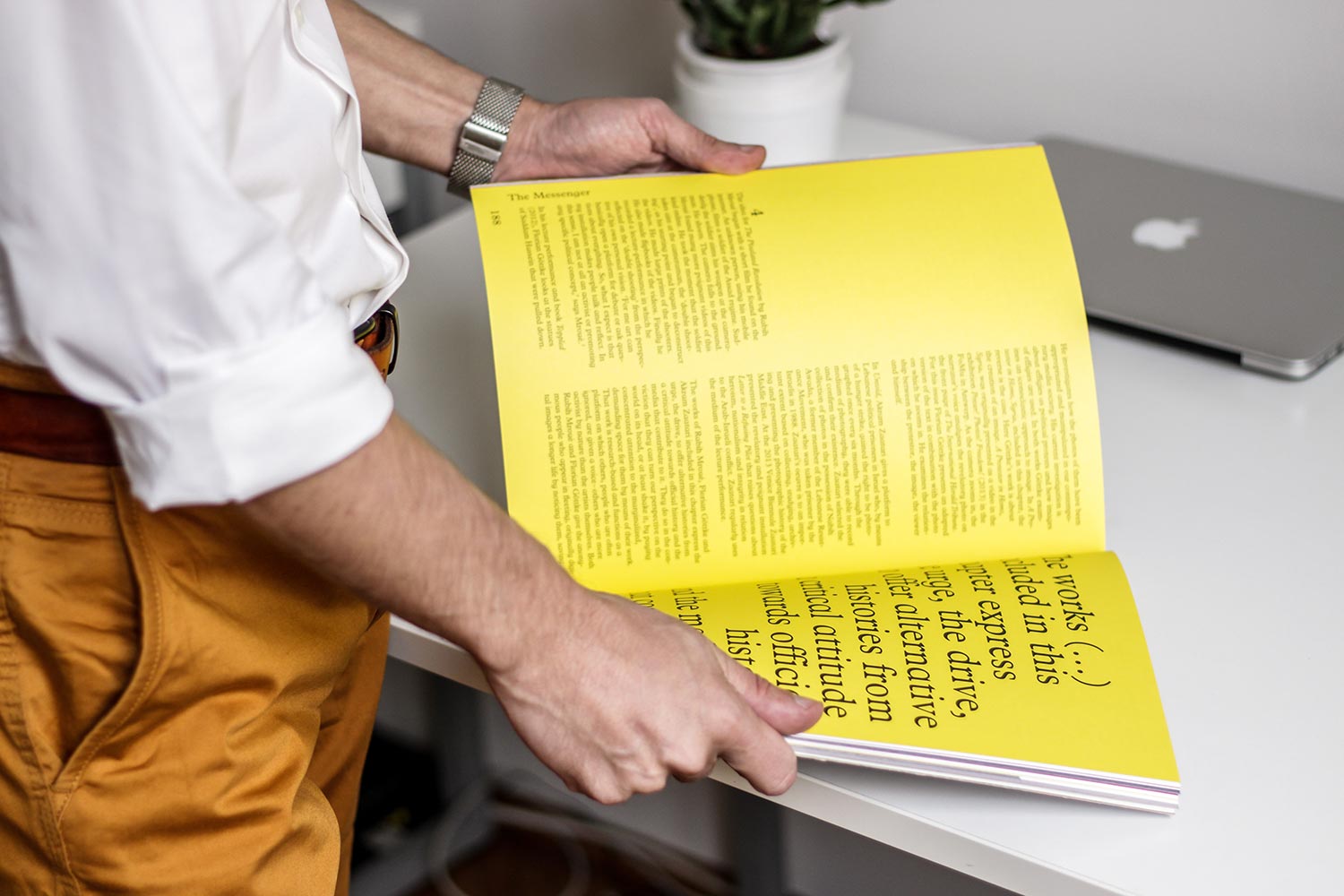

Editorial Design Inspiration

I collect the occasional editorial design inspiration in this collection. Other great resources for editorial design are Designspiration and Behance. Though, the best inspiration comes from buying the actual magazines.

Heftwerk

Heftwerk is a network of Berlin-based services for magazine makers (printer and shipper, mostly) that I helped create. I use these services to print and ship my own magazine and because they’ve now done this with several indie titles the process is getting a lot smoother. Get in touch with them to get a quote, and if you don’t mind, please tell them that you heard of them through me.

Indie Publishing Club

This is a simple Facebook group I created to help indie publishers connect and share ideas/challenges. It’s a member-only thing, and for the sake of keeping the discussion on topic, I only give access to existing publishers of print titles. So once you’ve got a first issue, make sure to join us!

Last, but not least, a reminder to keep browsing. I've written down most of my successes and failures on this blog. They might save you some mistakes. Also highly recommended, my Medium post Indie Magonomics.